This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 36, number 01 (2013). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

SYNOPSIS

To understand Voodoo as a culture and a religion, one must understand its history. Haiti has become a prominent figure for Voodoo because of its African cultural and religious heritage. Through the sixteenth-century slave-trade system, Africans were taken from West Africa to the West Indies to work as slaves on European plantations. They brought their religion with them. In spite of its oral tradition, the core beliefs and practices of Voodoo have been preserved over time and space. The similarities between Voodoo and traditional West African religion cannot be contested and have led to the understanding that it is indeed the same religion with minor variations influenced by syncretism, creativity, and diverse experiences. The core doctrines include beliefs in a Supreme Being who can only be worshipped through secondary divinities that emanate from Him, from nature, and from deified ancestors. Its practices range from healing through homeopathic or natural remedies or potions prepared for a variety of symptoms to magic, witchcraft, and sorcery. A careful analysis of the doctrine and practices of Voodoo leads to the conclusion that Voodoo is more polytheistic than it claims to be and that its practices, worship, and way of life are incompatible with the Christian faith.

On January 12, 2010, a devastating earthquake caused the worst disaster in Haitian history. Three hundred thousand people lost their lives. The day after the earthquake, a prominent evangelical leader in the United States made statements that linked the devastating earthquake to a “pact” that Haitians allegedly made with the Devil during a Voodoo ceremony.1

Apart from off-the-cuff comments such as those, there has been a seemingly total indifference among evangelical Christians to the subject of Voodoo. Still, it is a religion that is practiced by millions of adherents throughout the world—particularly in Africa and the Caribbean—but also in the United States, especially Louisiana. Voodoo deserves some clarification and it is worth noting the relationship to Christianity in terms of compatibility and irreconcilable differences for the purpose of effective evangelism and discipleship.

The study of Voodoo as a religion is difficult for several reasons. First, it is a religion that is based on oral tradition with no written text. Recent initiatives to provide some definition to its beliefs and practices had to rely on the oral tradition. Second, there is much room for disagreement as to the very nature of the religion itself. For example: even on the basis of a surface analysis, is Voodoo a good or evil religion? Some adherents would admit to the practices of witchcraft and magic for evil purposes; others attempt to detach it from anything evil.

ORIGINS AND HISTORY OF VOODOO

Most of the beliefs and practices of Voodoo can be traced back to aspects of traditional African religion and culture. It is practiced in the Caribbean, Central, North, and South America in various forms. Because of its history, however, Haiti has emerged as the primary place for the development and evolution of Voodoo.

Christopher Columbus discovered Haiti in 1492. At that time, the inhabitants were Arawak Indians who called the land Ayiti because of its mountains. It was rich in gold and potential for growing crops such as sugar cane, cotton, cocoa, and coffee. In the sixteenth century, the island became a land of exploration and exploitation for Europeans, particularly the Spaniards, and then the French. When those natural resources became in high demand by European markets, the French looked to Africa for cheap labor. Through the slave- trade system, countless numbers of Africans were shipped to Haiti to work as slaves in the plantations under the most inhuman treatment imaginable.2

The Africans were taken from various tribes, regions, and countries from the West Coast of Africa (Gulf of Guinea), from areas known today as Senegal, Gambia, the Congo region, Nigeria, and Dahomey.3 A long list of regions and tribes contributed to the heterogeneity of the beliefs and practices of transplanted Africans.4

Although heterogeneous in many aspects, Voodoo has maintained some universal beliefs and practices that represent the core of the West African Traditional Religious system. According to Dr. P. A Ojebode, professor of comparative study of religion at the National Open University of Nigeria, the West African Traditional Religion (WATR) is part of the African heritage as a legacy bequeathed from the ancestors.

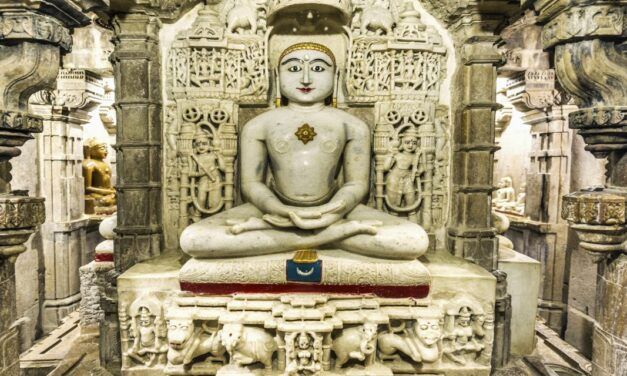

The WATR includes belief in a Supreme Being who cannot be approached by humans. WATR also holds that there are lesser divinities, spirits who emanated from the Supreme Deity and have attributes of the Supreme Being as His offspring. They serve as messengers or intermediaries between humans and the Supreme Being. The divinities are ranked in various categories. The primordial divinities are believed to be the divinities of heaven, others comprise the spirit of deified ancestors, and still other divinities are associated with mountains, rivers, and so on. By offering daily sacrifices to these intermediaries, people worship God through them. They have temples, shrines, priests, priestesses, and devotees. Each of those divinities has his or her specific sacred object. For instance, iron is the emblem of Ogun (a patron spirit or loa of fire). Other objects usually present in the shrine include calabashes, stones, carved images, pots, ax-heads, and metal snakes.

The WATR also includes belief in magic, witchcraft, and sorcery. According to Ojebode, magic and religion are not mutually exclusive; they both have existed alongside one another across centuries. Magic is a ritual activity that is believed to influence human or natural events through access to external mystical forces. It involves the manipulation of certain objects to cause a supernatural being to produce or prevent a particular result that could not have been obtained otherwise. Witchcraft and sorcery are ugly realities that tend to be ignored by the scientifically inclined or those who want to present Voodoo in the best light possible. Yet they represent the evil side of the tradition. They are employed to inflict misfortunes, accidents, sudden deaths, poverty, barrenness, and other human miseries. Life and property can be cursed. Practitioners may attempt to kill a victim by means of invocation through homeopathic magic. A sorcerer may curse his victim, who may become insane or commit suicide. There is distinction within WATR between those who practice homeopathic or natural medicines, magic, witchcraft, and sorcery. However, witchcraft and sorcery are powers believed to have been inherited from the divinities.5

All the scholars who have studied Voodoo agree that Voodoo owes its origins to the WATR, or the Dahomean (from Dahomey, the former name of the west African country of Benin) culture. The theology and practices of WATR and Voodoo are strikingly similar. Although many, such as Jean- Price Mars, have argued that Voodoo is a religion in its own right because it has its own theology and its own ethic, they would concede that it is from the richness of the African culture that Haiti has developed a distinct culture through syncretism, cultural creativity, and assimilation.6

HISTORY OF VOODOO IN HAITI

When the slaves arrived in Haiti in the sixteenth century, they were forbidden to practice their faith publicly. The slave owners were predominantly Catholic and they devised a plan to maintain slavery through catechism and conversion to Christianity. The slaves were not allowed to gather for any purpose, however, including Christian religious services, lest such gatherings should lead to uprisings. Fearing that the teaching of Christianity might instill in the slaves a concept of human dignity that was inconsistent with slavery, they introduced the slaves to only the basic elements of the Christian faith. Yet the slaves maintained their original beliefs by finding similarities between what was being taught from Catholicism and the traditional African religion. Although baptized into Catholicism, the slaves were not truly converted into a religion whose adherents were treating them like beasts.7

The resistance of the slaves to being truly converted to Catholicism is nowhere more manifest than in the historical gathering called Ceremony of Bois Caiman. The importance of Voodoo in attaining Haitian independence, as well as the historiography of the Bwa Kayiman ceremony, has been articulated largely by Haitian and foreign intellectuals as well as other observers.8 “During the night of August 14, 1791 in the midst of a forest called Bois Caïman [Alligator Wood], on the Morne Rouge in the northern plain, near Cap-Haitian, Haiti, the slaves held a large meeting to draw up a final plan for a general revolt. Presiding over the assembly was a black man named Boukman, whose fiery words exalted the conspirators….A black pig was sacrificed. And everybody in assistance swore blindly to obey the orders of Boukman, who had been proclaimed the supreme chief of the rebellion.”9

The Bois Caiman ceremony is an undeniable event in the history of Haitian freedom from slavery. However, no historian has ever reported a “pact with the Devil” at that ceremony. The gathering gave the slaves the collective determination and the courage drawn from their beliefs that led to the sacrificing of an animal to their gods. Animal sacrifices are common in Voodoo ceremonies. The gathering was a reaction to the oppressive slave owners and a foreign religion that was being forced on them in order to keep them in the inhumane condition of slavery. It was the courage and determination of the slaves who vowed to live free or die that made Haiti the first independent black nation of the world—not a “pact with the Devil.”

After the abolition of slavery, Voodoo was suppressed by the three most important figures of the Haitian Independence. The first Constitution of Haiti made Catholicism the official religion of the State of Haiti, with all official political and governmental ceremonies and commemorations beginning with a Mass celebrated at the Catholic Church.10 Still, many practiced Voodoo alongside Catholicism, with similar devotion to both.

Since Voodoo has been received as an integral part of the African Cultural Heritage, any attempt to suppress it has been interpreted as an attack against Haitian identity. Efforts by Haitian writers to return Haiti to the African Traditions were long countered by Roman Catholic campaigns against Voodoo and its superstitious beliefs, but by the early 1950s, the Catholic Church decided to make peace with Voodoo.11 In 1987, one year after the end of the dictatorial regime of the Duvaliers, the New Constitution of Haiti afforded Voodoo the same right and social status as any other religion practiced in Haiti. In April 2003, by decree of then President Jean-Bertrand Aristide (a Catholic priest), Voodoo was elevated to the same legal position as the other religions of the country. In his decree, President Aristide stated, “Voodoo is an essential part of [Haitian] national identity.”12

In March 2008, the National Conference of Haitian Voodoo elected its founder, Max Beauvoir, as the first Supreme Spiritual Leader or Supreme Chief of Voodoo, called an ATI, meaning an Elder. Beauvoir, a biochemist who studied in renowned European and American universities, specialized in herbal medicine. The presence of Beauvoir in the Voodoo scene has been significant in the evolution of Voodoo in Haiti. He wrote two books that he calls national patrimonies of a religion that had no standard text defining its beliefs and practices.

During an interview given on TeleImage, a Haitian television program based in Long Island, New York, Beauvoir made some significant revelations about Voodoo as a religion. First, he reaffirmed the basic beliefs of Voodoo taken directly from the West African Traditional religious system and culture. They include belief in a Supreme Being who gives powers to intermediary divinities between Him and man. Those divinities are called loas, or spirits who represent expressions of the Supreme Being.

Second, Beauvoir sees syncretism as an incorporation of various rites and beliefs in the service of Voodoo from various religions and tribes. Some of the practices come from the Arawak Indians who first inhabited the land.

Third, contrary to those who wish to detach Voodoo from evil tendencies, Beauvoir openly admitted the practices of magic, sorcery, and witchcraft as part of the tradition. For instance, he discussed the process of Zombification practiced by a secret society called the Sanpwel. They operate at night and seek to use magic powers to cause evil against those who might have committed a crime in or against the community.13

I also interviewed a Voodoo priestess, Dr. Lunine Pierre-Jerome, an educator with a Ph.D. from the University of Massachusetts. She is proud of her Voodoo heritage and sees it as part of her identity. She has practiced Voodoo for more than twenty years. She affirmed beliefs similar to the African Tradition and Beauvoir, except for the practices of evil. While she did not deny that such evil practices occur, Pierre-Jerome does not see them as inherent to Voodoo as a religion. She maintains that every religion has some evil elements in it. She also points out that Catholic prayers, such as “Hail Mary” and the “Pater Noster,” are used before transitioning to the prayers to the “Loas” during their services.14

VOODOO AS CULTURE AND RELIGION: THE CHRISTIAN RESPONSE

Understanding the West African Heritage of Haitian culture and Voodoo is important in determining the appropriate evangelical approach to Voodoo as a culture and a religion.

Open dialogue must begin with the acknowledgement that the dynamic ways in which religious and cultural values interact are not readily understood without profound study, analysis, and discernment. There is a fine line between rejecting legitimate aspects of culture in the name of evangelism and adopting sinful elements of culture in the name of enculturation and tolerance.

Culture is defined as “the integrated pattern of human knowledge, belief, and behaviors that depends upon man’s capacity for learning and transmitting knowledge to succeeding generations.”15 In culture there are values, beliefs, customs, and traditions that define and shape the lives of the people in any given society. Since the fall of Adam, human nature—and consequently the culture it creates—has been corrupted and permeated by sin. As such, there is a need for a theology of culture to understand any given culture and to propose a relevant, biblical response to it. Culture should not be ignored, automatically discarded, or rejected. It must be carefully studied in light of Scripture to discern both areas of compatibility and of irreconcilable differences. We must never have a cultural view of what is biblical, but rather a biblical view of what is cultural. Voodoo should not escape such scrutiny because of the fear of losing one’s cultural identity.

ASSESSING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN VOODOO AND CHRISTIANITY

Much of the attempts made in the evaluation of the relationship between Voodoo and Christianity have centered on the concept of syncretism. Their failure is often based on superficial comparison of languages, rituals, terminologies, and certain behaviors that are borrowed or transferred from one faith to another. The study of relationships between two religions must be based on the doctrines that define their beliefs and practices in terms of their view of God, their standard of practices, the standard code of ethics, and other fundamental issues.

THE THEOLOGY OF VOODOO

According to the literature and as reaffirmed by Beauvoir and Jerome, Voodoo is a monotheistic religion that believes in the Supreme Being. Still one must ask, are Gran Met (Great Master), the god of Voodoo, and Yahweh, the God of the Bible, different names for the same God? Nothing in Voodoo theology describes the true nature of Gran Met, how he is revealed to his adherents, and how he should be worshipped.

The admission of the existence of the loas or lesser divinities who serve as intermediaries between humans and this transcendent Supreme Being makes Voodoo more polytheistic than it appears. Voodoo divinities, unlike angels, are worshipped and served as substitutes or surrogates to Gran Met. The Christian faith forbids the worship of any other god, as stated in the very first commandment (Exod. 20:3), and this applies also to angels and departed humans (e.g., Rev. 22:8–9). The idea of lesser divinities as intermediaries is also inconsistent with Christian theology. There is one mediator between God and man—Jesus Christ, the Way, the Truth, and the Life (1 Tim. 2:5; John 14:6). The Gran Met of Voodoo is not the God of the Bible. The god of Voodoo is Satan, who through various schemes has infiltrated the culture and religion to create distortions in terminologies and practices to cause humanity to worship him and his demons in the place of the only true God.

THE PRACTICES OF VOODOO

One of the difficulties in defining Voodoo beliefs has to do with the lack of a standard source of authority that explains its doctrines. The beliefs and practices of Voodoo have passed from one generation to the next through oral tradition. In the absence of standard authority, relativism abounds in both the beliefs and practices of Voodoo. Until the recent publication of La Priye Ginen and Recueil de Chants Sacres by Beauvoir, no text could be evaluated to determine the fundamental authority behind the beliefs and practices of Voodoo. The way of worship in Voodoo involves the use of divine symbols. Such practices violate biblical faith, which states that no representations of God should be made as a means of worship (Exod. 20:4–6).

For Christians, the character of God as revealed in the Bible is the basis of morality and the commands and teachings of Scripture provide a clear moral standard. In Voodoo, however, the lack of a standard of doctrines leads to the lack of a standard of ethics. Although the concept of crime exists in their vocabulary, it seems to refer primarily to behaviors that are sanctioned by the community in which one lives. There is no clear moral standard or concept of sin. Evil magic can be applied to people or objects; life and property can be destroyed for personal satisfaction, vengeful purposes, or personal advantages.16

IRRECONCILABLE DIFFERENCES

As we have seen, there are fundamental differences between Voodoo and Christianity that make them irreconcilable. The Christian belief in a Triune God who alone is worthy of worship is contrary to the Voodoo concept of the Gran Met (Great Master) who is worshipped through a pantheon of lesser divinities that include the spirit of deceased relatives, the gods of Africa, and the Kreyol loas of Haiti. The god of Voodoo is not the God of the Bible; it is rather Satan who through various distortions and counterfeits disguises himself and infiltrates the culture and the religion to be worshipped in temples and shrines in the place of God (see, e.g., 1 Cor. 10:19–20). There is one mediator between God and man: Jesus Christ. The use of symbols is idolatrous and forbidden in Scripture. The practices of necromancy, divination, witchcraft, magic, and sorcery of the secret societies of Voodoo are incompatible with the Christian faith (see, e.g., Deut. 18:9–14).

For the purpose of effective evangelism, there is a need to study the Haitian culture and the Voodoo religion to understand its beliefs and practices. The dynamic between religion and culture and the values they share renders the task of evangelists, missionaries, and church leaders a very delicate one. The tendency to interpret Scriptures in light of a culture always comes into question when dealing with the interaction of faith and culture. However, one must develop an ability to distinguish between cultural beliefs and practices that can be adapted to a biblical worldview and those that cannot. Confusion and distortions of biblical beliefs and practices through syncretism should be corrected through discipleship of the new converts from Voodoo to help them understand what is pleasing and displeasing to God, and that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone, to the glory of God alone.

J. A. Alexandre is originally from Haiti. He has lived in the Unites States for the past thirty years. He holds academic degrees from Dallas Theological Seminary (Th.M., D.Min.) and George Fox University (Doctorate in Clinical Psychology). He is the Senior Pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Congregation, in the Boston area of Massachusetts.

NOTES

- cbn.com/about//pressrelease_patrobertson_haiti.aspx. Accessed January 13, 2010.

- Fridolin Saint–Louis, Le Voudou Haitien: Reflet d’une Societe Bloquee (Paris: L’Hartmatan, 2000), 39.

- Severine Singh, “A Brief History of Voodoo,” New Orleans Voodoo Crossroads (Cincinnati: Black Moon Publishing, 1994).

- Alfred Metraux, Voodoo in Haiti (New York: Shocken Books, 1989), 38.

- P. A. Ojebode, Course Code: CTH 202, Course Outline: Comparative Study of Religion, National Open University of Nigeria School of Arts and Social Sciences.

- Jean Price-Mars, Ainsi Parla L’oncle (Essais d’Ethnographie) (Paris: Imprimerie de Compiegne, 1928), 229. Witchcraft and sorcery are ugly realities that tend to be ignored by the scientifically inclined or those who want to present Voodoo in the best light possible.

- Fridolin, Le Voudou Haitien, 23.

- Markel Thylefors, “’Our Government Is in Bwa Kayiman’: A Vodou Ceremony in 1791 and Its Contemporary Significations,” Stockholm Review of Latin American Studies, issue 4 (March 2009): 74.

- Ibid. 75.

- Michel S. Laguerre, Voodoo and Politics in Haiti (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 5.

- James Leyburn, The Haitian People (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966), 118.

- Michael Norton, “Haiti Officially Sanctions Voodoo,” Global Black News, April 11, 2003, 1.

- Max Beauvoir, interview with Valerio Saint-Louis (Long Island, NY: TeleImage), available on YouTube at www.youtube.com/watch?v=wx26H7nyoFE. Accessed August 14, 2012.

- Lunine Pierre-Jerome, Ph.D, interviewed by this author in August 2012.

- Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 8th ed. (Springfield, MA: Merriam, 1987), 314.

- O. Imasogie, African Traditional Religion (Ibadan, Nigeria: Ibadan University Press, 1985), 57–59.