This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 13, number 02 (1990). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

Popular opinion often comes from obscure sources. Many conceptions about Jesus now current and credible in New Age circles are rooted in a movement of spiritual protest which, until recently, was the concern only of the specialized scholar or the occultist. This ancient movement — Gnosticism — provides much of the form and color for the New Age portrait of Jesus as the illumined Illuminator: one who serves as a cosmic catalyst for others’ awakening.

Many essentially Gnostic notions received wide attention through the sagacious persona of the recently deceased Joseph Campbell in the television series and best-selling book, The Power of Myth. For example, in discussing the idea that “God was in Christ,” Campbell affirmed that “the basic Gnostic and Buddhist idea is that that is true of you and me as well.” Jesus is an enlightened example who “realized in himself that he and what he called the Father were one, and he lived out of that knowledge of the Christhood of his nature.” According to Campbell, anyone can likewise live out his or her Christ nature.1

Gnosticism has come to mean just about anything. Calling someone a Gnostic can make the person either blush, beam, or fume. Whether used as an epithet for heresy or spiritual snobbery, or as a compliment for spiritual knowledge and esotericism, Gnosticism remains a cornucopia of controversy.

This is doubly so when Gnosticism is brought into a discussion of Jesus of Nazareth. Begin to speak of “Christian Gnostics” and some will exclaim, “No way! That is a contradiction in terms. Heresy is not orthodoxy.” Others will affirm, “No contradiction. Orthodoxy is the heresy. The Gnostics were edged out of mainstream Christianity for political purposes by the end of the third century.” Speak of the Gnostic Christ or the Gnostic gospels, and an ancient debate is moved to the theological front burner.

Gnosticism as a philosophy refers to a related body of teachings that stress the acquisition of “gnosis,” or inner knowledge. The knowledge sought is not strictly intellectual, but mystical; not merely a detached knowledge of or about something, but a knowing by acquaintance or participation. This gnosis is the inner and esoteric mystical knowledge of ultimate reality. It discloses the spark of divinity within, thought to be obscured by ignorance, convention, and mere exoteric religiosity.

This knowledge is not considered to be the possession of the masses but of the Gnostics, the Knowers, who are privy to its benefits. While the orthodox “many” exult in the exoteric religious trappings which stress dogmatic belief and prescribed behavior, the Gnostic “few” pierce through the surface to the esoteric spiritual knowledge of God. The Gnostics claim the Orthodox mistake the shell for the core; the Orthodox claim the Gnostics dive past the true core into a nonexistent one of their own esoteric invention. To adjudicate this ancient acrimony requires that we examine Gnosticism’s perennial allure, expose its philosophical foundations, size up its historical claims, and square off the Gnostic Jesus with the figure who sustains the New Testament.

MODERN GNOSTICISM

Gnosticism is experiencing something of a revival, despite its status within church history as a vanquished Christian heresy. The magazine Gnosis, which bills itself as a “journal of western inner traditions,” began publication in 1985 with a circulation of 2,500. As of September 1990, it sported a circulation of 11,000. Gnosis regularly runs articles on Gnosticism and Gnostic themes such as “Valentinus: A Gnostic for All Seasons.”

Some have created institutional forms of this ancient religion. In Palo Alto, California, priestess Bishop Rosamonde Miller officiates the weekly gatherings of Ecclesia Gnostica Myteriorum (Church of Gnostic Mysteries), as she has done for the last eleven years. The chapel holds forty to sixty participants each Sunday and includes Gnostic readings in its liturgy. Miller says she knows of twelve organizationally unrelated Gnostic churches throughout the world.2 Stephan Hoeller, a frequent contributor to Gnosis, who since 1967 has been a bishop of Ecclesia Gnostica in Los Angeles, notes that “Gnostic churches…have sprung up in recent years in increasing numbers.”3 He refers to an established tradition of “wandering bishops” who retain allegiance to the symbolic and ritual form of orthodox Christianity while reinterpreting its essential content.4

Of course, these exotic-sounding enclaves of the esoteric are minuscule when compared to historic Christian denominations. But the real challenge of Gnosticism is not so much organizational as intellectual. Gnosticism in its various forms has often appealed to the alienated intellectuals who yearn for spiritual experience outside the bounds of the ordinary.

The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, a constant source of inspiration for the New Age, did much to introduce Gnosticism to the modern world by viewing it as a kind of proto-depth psychology, a key to psychological interpretation. According to Stephan Hoeller, author of The Gnostic Jung, “it was Jung’s contention that Christianity and Western culture have suffered grievously because of the repression of the Gnostic approach to religion, and it was his hope that in time this approach would be reincorporated in our culture, our Western spirituality.”5

In his Psychological Types, Jung praised “the intellectual content of Gnosis” as “vastly superior” to the orthodox church. He also affirmed that, “in light of our present mental development [Gnosticism] has not lost but considerably gained in value.”6

A variety of esoteric groups have roots in Gnostic soil. Madame Helena P. Blavatsky, who founded Theosophy in 1875, viewed the Gnostics as precursors of modern occult movements and hailed them for preserving an inner teaching lost to orthodoxy. Theosophy and its various spin-offs — such as Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, Alice Bailey’s Arcane School, Guy and Edna Ballard’s I Am movement, and Elizabeth Clare Prophet’s Church Universal and Triumphant — all draw water from this same well; so do various other esoteric groups, such as the Rosicrucians. These groups share an emphasis on esoteric teaching, the hidden divinity of humanity, and contact with nonmaterial higher beings called masters or adepts.

A four-part documentary called “The Gnostics” was released in mid-1989 and shown in one-day screenings across the country along with a lecture by the producer. This ambitious series charted the history of Gnosticism through dramatizations and interviews with world-renowned scholars on Gnosticism such as Gilles Quispel, Hans Jonas, and Elaine Pagels. A review of the series in a New Age-oriented journal noted: “The series takes us to the Nag Hammadi find where we learn the beginnings of the discovery of texts called the Gnostic Gospels that were written around the same time as the gospels of the New Testament but which were purposely left out.”7 The review refers to one of the most sensational and significant archaeological finds of the twentieth century; a discovery seen by some as overthrowing the orthodox view of Jesus and Christianity forever.

GOLD IN THE JAR

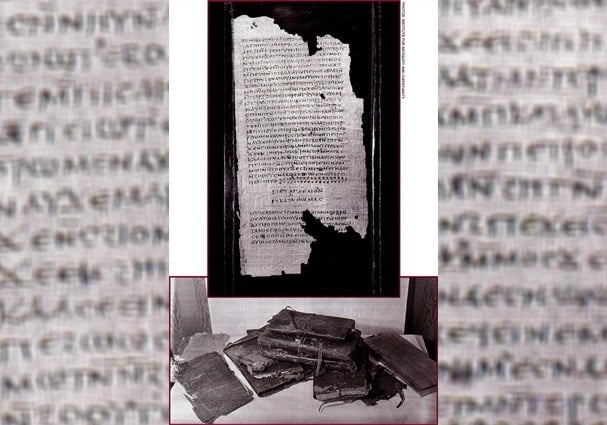

In December 1945, while digging for soil to fertilize crops, an Arab peasant named Muhammad ‘Ali found a red earthenware jar near Nag Hammadi, a city in upper Egypt. His fear of uncorking an evil spirit or jin was shortly overcome by the hope of finding gold within. What was found has been for hundreds of scholars far more precious than gold. Inside the jar were thirteen leather-bound papyrus books (codices), dating from approximately A.D. 350. Although several of the texts were burned or thrown out, fifty-two texts were eventually recovered through many years of intrigue involving illegal sales, violence, smuggling, and academic rivalry.

Some of the texts were first published singly or in small collections, but the complete collection was not made available in a popular format in English until 1977. It was released as The Nag Hammadi Library and was reissued in revised form in 1988.

Although many of these documents had been referred to and denounced in the writings of early church theologians such as Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, most of the texts themselves had been thought to be extinct. Now many of them have come to light. As Elaine Pagels put it in her best-selling book, The Gnostic Gospels, “Now for the first time, we have the opportunity to find out about the earliest Christian heresy; for the first time, the heretics can speak for themselves.”8

Pagels’s book, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award, arguably did more than any other effort to ingratiate the Gnostics to modern Americans. She made them accessible and even likeable. Her scholarly expertise coupled with her ability to relate an ancient religion to contemporary concerns made for a compelling combination in the minds of many. Her central thesis was simple: Gnosticism should be considered at least as legitimate as orthodox Christianity because the “heresy” was simply a competing strain of early Christianity. Yet, we find that the Nag Hammadi texts present a Jesus at extreme odds with the one found in the Gospels. Before contrasting the Gnostic and biblical renditions of Jesus, however, we need a short briefing on gnosis.

THE GNOSTIC MESSAGE

Gnosticism in general and the Nag Hammadi texts in particular present a spectrum of beliefs, although a central philosophical core is roughly discernible, which Gnosticism scholar Kurt Rudolph calls “the central myth.”9 Gnosticism teaches that something is desperately wrong with the universe and then delineates the means to explain and rectify the situation.

The universe, as presently constituted, is not good, nor was it created by an all-good God. Rather, a lesser god, or demiurge (as he is sometimes called), fashioned the world in ignorance. The Gospel of Philip says that “the world came about through a mistake. For he who created it wanted to create it imperishable and immortal. He fell short of attaining his desire.”10 The origin of the demiurge or offending creator is variously explained, but the upshot is that some precosmic disruption in the chain of beings emanating from the unknowable Father-God resulted in the “fall out” of a substandard deity with less than impeccable credentials. The result was a material cosmos soaked with ignorance, pain, decay, and death — a botched job, to be sure. This deity, nevertheless, despotically demands worship and even pretentiously proclaims his supremacy as the one true God.

This creator-god is not the ultimate reality, but rather a degeneration of the unknown and unknowable fullness of Being (or pleroma). Yet, human beings — or at least some of them — are in the position potentially to transcend their imposed limitations, even if the cosmic deck is stacked against them. Locked within the material shell of the human race is the spark of this highest spiritual reality which (as one Gnostic theory held) the inept creator accidently infused into humanity at the creation — on the order of a drunken jeweler who accidently mixes gold dust into junk metal. Simply put, spirit is good and desirable; matter is evil and detestable.

If this spark is fanned into a flame, it can liberate humans from the maddening matrix of matter and the demands of its obtuse originator. What has devolved from perfection can ultimately evolve back into perfection through a process of self-discovery.

Into this basic structure enters the idea of Jesus as a Redeemer of those ensconced in materiality. He comes as one descended from the spiritual realm with a message of self-redemption. The body of Gnostic literature, which is wider than the Nag Hammadi texts, presents various views of this Redeemer figure. There are, in fact, differing schools of Gnosticism with differing Christologies. Nevertheless, a basic image emerges.

The Christ comes from the higher levels of intermediary beings (called aeons) not as a sacrifice for sin but as a Revealer, an emissary from error-free environs. He is not the personal agent of the creator-god revealed in the Old Testament. (That metaphysically disheveled deity is what got the universe into such a royal mess in the first place.) Rather, Jesus has descended from a more exalted level to be a catalyst for igniting the gnosis latent within the ignorant. He gives a metaphysical assist to underachieving deities (i.e., humans) rather than granting ethical restoration to God’s erring creatures through the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

NAG HAMMADI UNVEILED

By inspecting a few of the Nag Hammadi texts, we encounter Gnosticism in Christian guise: Jesus dispenses gnosis to awaken those trapped in ignorance; the body is a prison, and the spirit alone is good; and salvation comes by discovering the “kingdom of God” within the self.

One of the first Nag Hammadi texts to be extricated out of Egypt and translated into Western tongues was the Gospel of Thomas, comprised of one hundred and fourteen alleged sayings of Jesus. Although scholars do not believe it was actually written by the apostle Thomas, it has received the lion’s share of scholarly attention. The sayings of Jesus are given minimal narrative setting, are not thematically arranged, and have a cryptic, epigrammatic bite to them. Although Thomas does not articulate every aspect of a full-blown Gnostic system, some of the teachings attributed to Jesus fit the Gnostic pattern. (Other sayings closely parallel or duplicate material found in the synoptic Gospels.)

The text begins: “These are the secret sayings which the living Jesus spoke and which Didymos Judas Thomas wrote down. And he said, ‘Whoever finds the interpretation of these sayings will not experience death.'”11 Already we find the emphasis on secret knowledge (gnosis) as redemptive.

JESUS AND GNOSIS

Unlike the canonical gospels, Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection are not narrated and neither do any of the hundred and fourteen sayings in the Gospel of Thomas directly refer to these events. Thomas’s Jesus is a dispenser of wisdom, not the crucified and resurrected Lord.

Jesus speaks of the kingdom: “The kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you. When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living father. But if you will not know yourselves, you dwell in poverty and it is you who are that poverty.”12

Other Gnostic documents center on the same theme. In the Book of Thomas the Contender, Jesus speaks “secret words” concerning self-knowledge: “For he who has not known himself has known nothing, but he who has known himself has at the same time already achieved knowledge of the depth of the all.”13

Pagels observes that many of the Gnostics “shared certain affinities with contemporary methods of exploring the self through psychotherapeutic techniques.”14 This includes the premises that, first, many people are unconscious of their true condition and, second, “that the psyche bears within itself the potential for liberation or destruction.”15

Gilles Quispel notes that for Valentinus, a Gnostic teacher of the second century, Christ is “the Paraclete from the Unknown who reveals…the discovery of the Self — the divine spark within you.”16

The heart of the human problem for the Gnostic is ignorance, sometimes called “sleep,” “intoxication,” or “blindness.” But Jesus redeems man from such ignorance. Stephan Hoeller says that in the Valentinian system “there is no need whatsoever for guilt, for repentance from so-called sin, neither is there a need for a blind belief in vicarious salvation by way of the death of Jesus.”17 Rather, Jesus is savior in the sense of being a “spiritual maker of wholeness” who cures us of our sickness of ignorance.18

Gnosticism on Crucifixion and Resurrection

Those Gnostic texts that discuss Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection display a variety of views that, nevertheless, reveal some common themes.

James is consoled by Jesus in the First Apocalypse of James: “Never have I suffered in any way, nor have I been distressed. And this people has done me no harm.”19

In the Second Treatise of the Great Seth, Jesus says, “I did not die in reality, but in appearance.” Those “in error and blindness….saw me; they punished me. It was another, their father, who drank the gall and vinegar; it was not I. They struck me with the reed; it was another, Simon, who bore the cross on his shoulder. I was rejoicing in the height over all….And I was laughing at their ignorance.”20

John Dart has discerned that the Gnostic stories of Jesus mocking his executors reverse the accounts in Matthew, Mark, and Luke where the soldiers and chief priests (Mark 15:20) mock Jesus.21 In the biblical Gospels, Jesus does not deride or mock His tormentors; on the contrary, while suffering from the cross, He asks the Father to forgive those who nailed Him there.

In the teaching of Valentinus and followers, the death of Jesus is movingly recounted, yet without the New Testament significance. Although the Gospel of Truth says that “his death is life for many,” it views this life-giving in terms of imparting the gnosis, not removing sin.22 Pagels says that rather than viewing Christ’s death as a sacrificial offering to atone for guilt and sin, the Gospel of Truth “sees the crucifixion as the occasion for discovering the divine self within.”23

A resurrection is enthusiastically affirmed in the Treatise on the Resurrection: “Do not think the resurrection is an illusion. It is no illusion, but it is truth! Indeed, it is more fitting to say that the world is an illusion rather than the resurrection.”24 Yet, the nature of the post-resurrection appearances differs from the biblical accounts. Jesus is disclosed through spiritual visions rather than physical circumstances.

The resurrected Jesus for the Gnostics is the spiritual Revealer who imparts secret wisdom to the selected few. The tone and content of Luke’s account of Jesus’ resurrection appearances is a great distance from Gnostic accounts: “After his suffering, he showed himself to these men and gave many convincing proofs that he was alive. He appeared to them over a period of forty days and spoke about the kingdom of God” (Acts 1:3).

By now it should be apparent that the biblical Jesus has little in common with the Gnostic Jesus. He is viewed as a Redeemer in both cases, yet his nature as a Redeemer and the way of redemption diverge at crucial points. We shall now examine some of these points.

DID CHRIST REALLY SUFFER AND DIE?

As in much modern New Age teaching, the Gnostics tended to divide Jesus from the Christ. For Valentinus, Christ descended on Jesus at his baptism and left before his death on the cross. Much of the burden of the treatise Against Heresies, written by the early Christian theologian Irenaeus, was to affirm that Jesus was, is, and always will be, the Christ. He says: “The Gospel…knew no other son of man but Him who was of Mary, who also suffered; and no Christ who flew away from Jesus before the passion; but Him who was born it knew as Jesus Christ the Son of God, and that this same suffered and rose again.”25

Irenaeus goes on to quote John’s affirmation that “Jesus is the Christ” (John 20:31) against the notion that Jesus and Christ were “formed of two different substances,” as the Gnostics taught.26

In dealing with the idea that Christ did not suffer on the cross for sin, Irenaeus argues that Christ never would have exhorted His disciples to take up the cross if He in fact was not to suffer on it Himself, but fly away from it.27

For Irenaeus (a disciple of Polycarp, who himself was a disciple of the apostle John), the suffering of Jesus the Christ was paramount. It was indispensable to the apostolic “rule of faith” that Jesus Christ suffered on the cross to bring salvation to His people. In Irenaeus’s mind, there was no divine spark in the human heart to rekindle; self-knowledge was not equal to God-knowledge. Rather, humans were stuck in sin and required a radical rescue operation. Because “it was not possible that the man…who had been destroyed through disobedience, could reform himself,” the Son brought salvation by “descending from the Father, becoming incarnate, stooping low, even to death, and consummating the arranged plan of our salvation.”28

This harmonizes with the words of Polycarp: “Let us then continually persevere in our hope and the earnest of our righteousness, which Jesus Christ, “who bore our sins in His own body on the tree” [1 Pet. 2:24], “who did no sin, neither was guile found in his mouth” [1 Pet. 2:22], but endured all things for us, that we might live in Him.”29

Polycarp’s mentor, the apostle John, said: “This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us” (1 John 3:16); and “This is love: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins” (4:10).

The Gnostic Jesus is predominantly a dispenser of cosmic wisdom who discourses on abstruse themes like the spirit’s fall into matter. Jesus Christ certainly taught theology, but he dealt with the problem of pain and suffering in a far different way. He suffered for us, rather than escaping the cross or lecturing on the vanity of the body.

THE MATTER OF THE RESURRECTION

For Gnosticism, the inherent problem of humanity derives from the misuse of power by the ignorant creator and the resulting entrapment of souls in matter. The Gnostic Jesus alerts us to this and helps rekindle the divine spark within. In the biblical teaching, the problem is ethical; humans have sinned against a good Creator and are guilty before the throne of the universe.

For Gnosticism, the world is bad, but the soul — when freed from its entrapments — is good. For Christianity, the world was created good (Gen. 1), but humans have fallen from innocence and purity through disobedience (Gen. 3; Rom. 3). Yet, the message of the gospel is that the One who can rightly prosecute His creatures as guilty and worthy of punishment has deigned to visit them in the person of His only Son — not just to write up a firsthand damage report, but to rectify the situation through the Cross and the Resurrection.

In light of these differences, the significance of Jesus’ literal and physical resurrection should be clear. For the Gnostic who abhors matter and seeks release from its grim grip, the physical resurrection of Jesus would be anticlimactic, if not absurd. A material resurrection would be counterproductive and only recapitulate the original problem.

Jesus displays a positive attitude toward the Creation throughout the Gospels. In telling His followers not to worry He says, “Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them” (Matt. 2:26). And, “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from the will of your Father” (Matt. 10:29). These and many other examples presuppose the goodness of the material world and declare care by a benevolent Creator. Gnostic dualism is precluded.

If Jesus recommends fasting and physical self-denial on occasion, it is not because matter is unworthy of attention or an incorrigible roadblock to spiritual growth, but because moral and spiritual resolve may be strengthened through periodic abstinence (Matt. 6:16-18; 9:14-15). Jesus fasts in the desert and feasts with His disciples. The created world is good, but the human heart is corrupt and inclines to selfishly misuse a good creation. Therefore, it is sometimes wise to deny what is good without in order to inspect and mortify what is bad within.

If Jesus is the Christ who comes to restore God’s creation, He must come as one of its own, a bona fide man. Although Gnostic teachings show some diversity on this subject, they tend toward docetism — the doctrine that the descent of the Christ was spiritual and not material, despite any appearance of materiality. It was even claimed that Jesus left no footprints behind him when he walked on the sand.

From a biblical view, materiality is not the problem, but disharmony with the Maker. Adam and Eve were both material and in harmony with their good Maker before they succumbed to the Serpent’s temptation. Yet, in biblical reasoning, if Jesus is to conquer sin and death for humanity, He must rise from the dead in a physical body, albeit a transformed one. A mere spiritual apparition would mean an abdication of material responsibility. As Norman Geisler has noted, “Humans sin and die in material bodies and they must be redeemed in the same physical bodies. Any other kind of deliverance would be an admission of defeat….If redemption does not restore God’s physical creation, including our material bodies, then God’s original purpose in creating a material world would be frustrated.”30

For this reason, at Pentecost the apostle Peter preached Jesus of Nazareth as “a man accredited by God to you by miracles, wonders and signs” (Acts 2:22) who, though put to death by being nailed to the cross, “God raised him from the dead, freeing him from the agony of death, because it was impossible for death to keep its hold on him” (v. 24). Peter then quotes Psalm 16:10 which speaks of God not letting His “Holy One see decay” (v. 27). Peter says of David, the psalm’s author, “Seeing what was ahead, he spoke of the resurrection of Christ, that he was not abandoned to the grave nor did his body see decay. God raised Jesus to life” (vv. 31, 32).

The apostle Paul confesses that if the resurrection of Jesus is not a historical fact, Christianity is a vanity of vanities (1 Cor. 15:14-19). And, while he speaks of Jesus’ (and the believers’) resurrected condition as a “spiritual body,” this does not mean nonphysical or ethereal; rather, it refers to a body totally free from the results of sin and the Fall. It is a spirit-driven body, untouched by any of the entropies of evil. Because Jesus was resurrected bodily, those who know Him as Lord can anticipate their own resurrected bodies.

JESUS, JUDAISM, AND GNOSIS

The Gnostic Jesus is also divided from the Jesus of the Gospels over his relationship to Judaism. For Gnostics, the God of the Old Testament is somewhat of a cosmic clown, neither ultimate nor good. In fact, many Gnostic documents invert the meaning of Old Testament stories in order to ridicule him. For instance, the serpent and Eve are heroic figures who oppose the dull deity in the Hypostasis of the Archons (the Reality of the Rulers) and in On the Origin of the World.31

In the Apocryphon of John, Jesus says he encouraged Adam and Eve to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil,32 thus putting Jesus diametrically at odds with the meaning of the Genesis account where this action is seen as the essence of sin (Gen. 3). The same anti-Jewish element is found in the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas where the disciples say to Jesus, “Twenty-four prophets spoke in Israel, and all of them spoke in you.” To which Jesus replies, “You have omitted the one living in your presence and have spoken (only) of the dead.”33 Jesus thus dismisses all the prophets as merely “dead.” For the Gnostics, the Creator must be separated from the Redeemer.

The Jesus found in the New Testament quotes the prophets, claims to fulfill their prophecies, and consistently argues according to the Old Testament revelation, despite the fact that He exudes an authority equal to it. Jesus says, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matt. 5:17). He corrects the Sadducees’ misunderstanding of the afterlife by saying, “Are you not in error because you do not know the Scriptures…” (Mark 12:24). To other critics He again appeals to the Old Testament: “You diligently study the Scriptures because you think that by them you possess eternal life. These are the Scriptures that testify about me” (John 5:39).

When Jesus appeared after His death and burial to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, He commented on their slowness of heart “to believe all that the prophets have spoken.” He asked, “Did not the Christ have to suffer these things and then enter into glory?” Luke then records, “And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself” (Luke 24:25-27).

For both Jesus and the Old Testament, the supreme Creator is the Father of all living. They are one and the same.

GOD: UNKNOWABLE OR KNOWABLE?

Many Gnostic treatises speak of the ultimate reality or godhead as beyond conceptual apprehension. Any hope of contacting this reality — a spark of which is lodged within the Gnostic — must be filtered through numerous intermediary beings of a lesser stature than the godhead itself.

In the Gospel of the Egyptians, the ultimate reality is said to be the “unrevealable, unmarked, ageless, unproclaimable Father.” Three powers are said to emanate from Him: “They are the Father, the Mother, (and) the Son, from the living silence.”34 The text speaks of giving praise to “the great invisible Spirit” who is “the silence of silent silence.”35 In the Sophia of Jesus Christ, Jesus is asked by Matthew, “Lord…teach us the truth,” to which Jesus says, “He Who Is is ineffable.” Although Jesus seems to indicate that he reveals the ineffable, he says concerning the ultimate, “He is unnameable….he is ever incomprehensible.”36

At this point the divide between the New Testament and the Gnostic documents couldn’t be deeper or wider. Although the biblical Jesus had the pedagogical tact not to proclaim indiscriminately, “I am God! I am God!” the entire contour of His ministry points to Him as God in the flesh. He says, “He who has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9). The prologue to John’s gospel says that “in the beginning was the Word (Logos)” and that “the Word was with God and was God” (John 1:1). John did not say, “In the beginning was the silence of the silent silence” or “the ineffable.”

Incarnation means tangible and intelligible revelation from God to humanity. The Creator’s truth and life are communicated spiritually through the medium of matter. “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling place among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only who came from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). The Word that became flesh “has made Him [the Father] known” (v. 19). John’s first epistle tells us: “The life appeared; we have seen it and testify to it, and we proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and has appeared to us. We proclaim to you what we have seen and heard…” (1 John 1:2-3).

Irenaeus encountered these Gnostic invocations of the ineffable. He quotes a Valentinian Gnostic teacher who explained the “primary Tetrad” (fourfold emanation from ultimate reality): “There is a certain Proarch who existed before all things, surpassing all thought, speech, and nomenclature” whom he called “Monotes” (unity). Along with this power there is another power called Hentotes (oneness) who, along with Monotes produced “an intelligent, unbegotten, and undivided being, which beginning language terms ‘Monad.'” Another entity called Hen (One) rounds out the primal union.37 Irenaeus satirically responds with his own suggested Tetrad which also proceeds from “a certain Proarch”:

But along with it there exists a power which I term Gourd; and along with this Gourd there exists a power which again I term Utter-Emptiness. This Gourd and Emptiness, since they are one, produced…a fruit, everywhere visible, eatable, and delicious, which fruit-language calls a Cucumber. Along with this Cucumber exists a power of the same essence, which again I call a Melon.38

Irenaeus’s point is well taken. If spiritual realities surpass our ability to name or even think about them, then any name under the sun (or within the Tetrad) is just as appropriate — or inappropriate — as any other, and we are free to affirm with Irenaeus that “these powers of the Gourd, Utter Emptiness, the Cucumber, and the Melon, brought forth the remaining multitude of the delirious melons of Valentinus.”39

Whenever a Gnostic writer — ancient or modern — simultaneously asserts that a spiritual entity or principle is utterly unknown and unnameable and begins to give it names and ascribe to it characteristics, we should hark back to Irenaeus. If something is ineffable, it is necessarily unthinkable, unreportable, and unapproachable.

ANCIENT GNOSTICISM AND MODERN THOUGHT

Modern day Gnostics, Neo-Gnostics, or Gnostic sympathizers should be aware of some Gnostic elements which decidedly clash with modern tastes. First, although Pagels, like Jung, has shown the Gnostics in a positive psychological light, the Gnostic outlook is just as much theological and cosmological as it is psychological. The Gnostic message is all of a piece, and the psychology should not be artificially divorced from the overall world view. In other words, Gnosticism should not be reduced to psychology — as if we know better what a Basilides or a Valentinus really meant than they did.

The Gnostic documents do not present their system as a crypto-psychology (with various cosmic forces representing psychic functions), but as a religious and theological explanation of the origin and operation of the universe. Those who want to adopt consistently Gnostic attitudes and assumptions should keep in mind what the Gnostic texts — to which they appeal for authority and credibility — actually say.

Second, the Gnostic rejection of matter as illusory, evil, or, at most, second-best, is at odds with many New Age sentiments regarding the value of nature and the need for an ecological awareness and ethic. Trying to find an ecological concern in the Gnostic corpus is on the order of harvesting wheat in Antarctica. For the Gnostics, as Gnostic scholar Pheme Perkins puts it, “most of the cosmos that we know is a carefully constructed plot to keep humanity from returning to its true divine home.”40

Third, Pagels and others to the contrary, the Gnostic attitude toward women was not proto-feminist. Gnostic groups did sometimes allow for women’s participation in religious activities and several of the emanational beings were seen as feminine. Nevertheless, even though Ms. Magazine gave The Gnostic Gospels a glowing review41, women fare far worse in Gnosticism than many think. The concluding saying from the Gospel of Thomas, for example, has less than a feminist ring:

Simon Peter said to them, “Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of life.”

Jesus said, “I myself shall lead her in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven.”42

The issue of the role of women in Gnostic theology and community cannot be adequately addressed here, but it should be noted that the Jesus of the Gospels never spoke of making the female into the male — no doubt because Jesus did not perceive the female to be inferior to the male. Going against social customs, He gathered women followers, and revealed to an outcast Samaritan woman that He was the Messiah — which scandalized His own disciples (John 4:1-39). The Gospels also record women as the first witnesses to Jesus’ resurrection (Matt. 28:1-10) — and this in a society where women were not considered qualified to be legal witnesses.

Fourth, despite an emphasis on reincarnation, several Gnostic documents speak of the damnation of those who are incorrigibly non-Gnostic43, particularly apostates from Gnostic groups.44 If one chafes at the Jesus of the Gospels warning of “eternal destruction,” chafings are likewise readily available from Gnostic doomsayers.

Concerning the Gnostic-Orthodox controversy, biblical scholar F. F. Bruce is so bold as to say that “there is no reason why the student of the conflict should shrink from making a value judgment: the Gnostic schools lost because they deserved to lose.”45 The Gnostics lost once, but do they deserve to lose again? We will seek to answer this in Part Two as we consider the historic reliability of the Gnostic (Nag Hammadi) texts versus that of the New Testament.

NOTES

- Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, ed. Betty Sue Flowers (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 210.

- Don Lattin, “Rediscovery of Gnostic Christianity,” San Francisco Chronicle, 1 April 1989, A-4-5.

- Stephan A. Hoeller, “Wandering Bishops,” Gnosis, Summer 1989, 24.

- Ibid.

- “The Gnostic Jung: An Interview with Stephan Hoeller,” The Quest, Summer 1989, 85.

- C. G. Jung, Psychological Types (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 11.

- “Gnosticism,” Critique, June-Sept. 1989, 66.

- Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Random House, 1979), xxxv.

- Kurt Rudolph, Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1987), 57f.

- James M. Robinson, ed., The Nag Hammadi Library (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1988), 154.

- Robinson, 126.

- F. F. Bruce, Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 112-13.

- Bentley Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., Inc., 1987), 403.

- Pagels, 124.

- Ibid., 126.

- Christopher Farmer, “An Interview with Gilles Quispel,” Gnosis, Summer 1989, 28.

- Stephan A. Hoeller, “Valentinus: A Gnostic for All Seasons,” Gnosis, Fall/Winter 1985, 24.

- Ibid., 25.

- Robinson, 265.

- Ibid., 365.

- John Dart, The Jesus of History and Heresy (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1988), 97.

- Robinson, 41.

- Pagels, 95.

- Robinson, 56.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.16.5.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 3.18.5.

- Ibid., 3.18.2.

- “The Epistle of Polycarp,” ch. 8, in The Apostolic Fathers, ed. A. Cleveland Coxe (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987), 35.

- Norman L. Geisler, “I Believe…In the Resurrection of the Flesh,” Christian Research Journal, Summer 1989, 21-22.

- See Dart, 60-74.

- Robinson, 117.

- Ibid., 132.

- Ibid., 209.

- Ibid., 210.

- Ibid., 224-25.

- Irenaeus, 1.11.3.

- Ibid., 1.11.4.

- Ibid.

- Pheme Perkins, “Popularizing the Past,” Commonweal, November 1979, 634.

- Kenneth Pitchford, “The Good News About God,” Ms. Magazine, April 1980, 32-35.

- Robinson, 138.

- See The Book of Thomas the Contender, in Robinson, 205.

- See Layton, 17.

- F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 277.

| GLOSSARY | exotericism: A pejorative term used by esotericists to describe the mere outer or popular understanding of spiritual truth which is supposedly inferior to the esoteric essence. |

| aeons: Emanations of Being from the unknowable, ultimate metaphysical principle or pleroma (see pleroma). | |

| Apostolic rule of faith: The essential teachings of the apostles that served as the authoritative standard for orthodox doctrine before the canonization of the New Testament. | gnosis: The Greek word for “knowledge” used by the Gnostics to mean knowledge gained not through intellectual discovery but through personal experience or acquaintance which initiates one into esoteric mysteries. The experience of gnosis reveals to the initiated the divine spark within. “Gnosis” has a very different meaning in the New Testament which excludes esotericism and self-deification. |

| Demiurge: According to the Gnostics (as opposed to Plato and others who had a more positive assessment), an inferior deity who ignorantly and incompetently fashioned the debased physical world. | |

| esotericism: The teaching that spiritual liberation is found in a secret or hidden knowledge (sometimes called gnosis) not available in traditional orthodoxy or exotericism. | Pleroma: The Greek word for “fulness” used by the Gnostics to mean the highest principle of Being where dwells the unknown and unknowable God. Used in the New Testament to refer to “fulness in Christ” (Col. 2:10) who is the known revelation of God in the flesh. |