***Note: The article discusses plot points of various Sherlock Holmes stories in book, television and movie formats which may be considered spoilers.***

This is an online-exclusive from the Christian Research Journal. For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

When you to subscribe to the Journal, you join the team of print subscribers whose paid subscriptions help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous detective stories offer much for the Christian reader of this journal to think about (or even research). Holmes is an able investigator. How can we also reason from scattered evidence toward causes? Holmes rules supernatural beings out of the scope of his investigations. When should the scientist (or detective) include supernatural causes in her worldly investigations? Holmes and Watson are fast friends. How is friendship necessary for a good life?1 These questions, however, are not the ones that are plaguing me today. Since my book on The Philosophy of Sherlock Holmes appeared, I’ve spotted a new mystery: Why has Sherlock turned into such a scoundrel these days?

In “The Final Problem,” Sherlock Holmes faces off against his nemesis, Professor Moriarty, at the Reichenbach Falls.2 In the struggle, Watson and the reader are led to believe that Holmes and Moriarty have plunged over the falls locked in mortal combat. Watson memorializes his friend’s exploits, concluding that his late friend was “the best and the wisest man whom I have ever known.” The words echo the death of Socrates in Plato’s Phaedo. It’s a touching tribute to what was, in the end, not the end of Sherlock Holmes.

After sacks full of hate mail and ten years’s time, Conan Doyle revived Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Empty House.” When Holmes reveals to Watson that he was still alive, he says, “I owe you a thousand apologies. I had no idea that you would be so affected.” It could perhaps be the author speaking to his fanbase, or the polite words of a clever (if emotionally obtuse) gentleman.

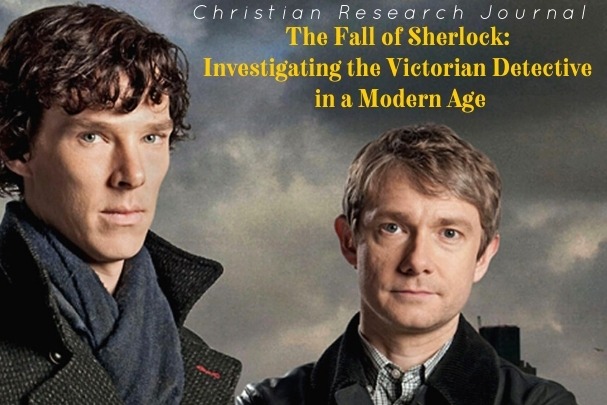

BBC’s series Sherlock (2010–2017) mirrors the basic pattern above, but with a key difference. When Holmes reveals to Watson in “The Empty Hearse” that he is still alive, he does so without a hint of apology or sympathy for Watson’s surprise. In fact, Holmes interrupts Watson’s planned proposal to his girlfriend with his stunt re-appearance. Earlier, Mycroft has warned Sherlock that Watson has “got on with his life.” “What life?” Sherlock responds, “I’ve been away.” Angrily questioning Sherlock after the revelation, Watson discovers that many others knew of Sherlock’s faked death.3 Keeping the secret from Watson, it seems, was not done out of necessity but rather out of thoughtlessness. It’s doubtful that Sherlock’s Holmes is quite the “high functioning sociopath” he calls himself in the series, but he’s certainly not the “best and wisest of men.”

Throughout the BBC series, Holmes is cleverly and incorrigibly rude to all around him. To Watson, but also to nearly anyone in his proximity. He dispels a little girl’s belief that her grandfather is in heaven: “People don’t really go to heaven when they die. They’re taken to a special room and burned.”4 He casually reveals two police officers are having an affair.5 He calls Watson and most other people idiots. In one particularly crushing scene, Holmes overlooks the tender advance of the medical examiner Molly Hooper, who is wearing lipstick for the occasion: “I was wondering if you’d like to have coffee?” “Black, two sugars please,” Holmes replies coldly.6 Despite these failings, Sherlock’s writing is so witty and Cumberbatch’s portrayal so unconventionally charismatic, we always love Holmes, even if we don’t like him or want to be like him.

A MODERN HERO

In many senses, Sherlock is just amplifying aspects of Conan Doyle’s literary creation: his occasional egotism, his slovenliness, his unconventional manners, and his sharp tongue. In the original short story that features Holmes’s return, which I quoted earlier, Holmes is quite short with Watson not long after their reunion. Watson comments, “Three years had certainly not smoothed the asperities of his temper or his impatience with a less active intelligence than his own.” In this regard, Sherlock Holmes is a modern hero: complicated and flawed. We watch Holmes grow in certain ways throughout the story. He overcomes his dangerous drug use. He tempers his sexism. After being bested by Irene Adler in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Watson writes, “He used to make merry over the cleverness of women, but I have not heard him do it of late.” Modern storytelling is enamored of flawed heroes who grow through struggle.

But there’s a shift in the characterization that goes beyond the intensification and acceleration of contemporary storytelling. Conan Doyle’s Holmes is, despite his flaws, still admirable. Holmes is a flawed hero. Modern portrayals of Sherlock seem to lean into his flaws so strongly that there is almost nothing to admire except his brilliance. The hero has become an anti-hero, or even worse. BBC’s Sherlock is not alone here. There is, of course, a grand history of lampooning the famous detective in comedy. Will Ferrell’s recent Holmes and Watson (2018) is just the newest entry. Most of the straightforward mysteries take Conan Doyle’s Sherlock down a few notches. 2020’s Enola Holmes painted a picture of a somewhat retiring and ineffectual Sherlock. More strikingly, Netflix’s recent series The Irregulars (2021) portrays Watson as a sinister conniver and Holmes as a shivering opium-addict. CBS’s Elementary (2012–2019) also leans into Holmes’s drug problem (a minor feature of the original stories), though with milder flaws.7

Perhaps the most popular and long-running recent TV series based on Sherlock Holmes is Fox’s House (2004–2012), which recasts Holmes as a doctor named House (get the joke?) and Watson as the supportive Wilson. Reframing Holmes as a doctor is fitting, as it is said that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself was inspired by one of his teachers from medical school, a Dr. Joseph Bell, a remarkably observant diagnostician who also dabbled in criminal investigations. Like BBC’s portrayal, House is insufferably rude and self-destructive. His opioid addiction and aggressive bedside manner make House borderline unemployable were it not for the brilliance he demonstrates weekly.

Now, I think it’s fair to say I’ve taken the long way around the barn to get to my main question: Why have our modern adaptations of Holmes become so critical? It may be, and I think this is a ready possibility, that as the most adapted literary hero in TV and film, modern storytellers have to offer a fresh spin, and the most natural spin is the rotation of water in the drain. In this regard, the darker takes on Holmes’s character have as much to do with belatedness as belittling. Something about Holmes’s quirks suggest that he’s circling self-destruction. In this sense, the later adaptations are merely picking up on features already embedded in Conan Doyle’s originals. Certainly, Sherlock and House have identified a mythic identity for a certain kind of anti-hero whose features and faults are both amplified to the max. In “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone,” Holmes said, “I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is mere appendix.” The recent adaptations, to create even more drama, have infected that appendix with cancer.

I think this is a plausible hypothesis, and is certainly a partial explanation, though I’m inclined to believe that there’s also a darker side to Sherlock’s modern decline. The rest of my account will be given over to exploring another culprit in the mysterious murder of Sherlock Holmes’s character.

A DARKER SIDE

Rereading Conan Doyle’s story for this piece, I was struck by many of the ways that Sherlock’s time and place feel modern. Though lit by gas and powered by steam, Sherlock’s London has quick communication, ample media coverage, and rapid travel by horse-drawn carriage and rail. It strikes me that part of the charm of Victorian London is how it is about the furthest back in time you can go and maintain most of the features of modern life.

The external similarity between Holmes’s world and ours, however, is deceptive. Rereading the canon, one finds little of contemporary crime fiction’s interest in what we might call “psychology” (abnormal, forensic, or otherwise). Most of Holmes’s understanding of human motivations is centered around character and self-interest. His villains typically act out of comprehensible self-interest in accordance with their virtues and vices. It is typically the details of the crimes that are complicated, not the motivations behind them. The moral axis of the Holmes canon is closely centered around virtue. Personal honor is prized highly by the admirable characters in Conan Doyle’s world. Small matters of manners are unimportant to Holmes, as is conformity to the law. Holmes is motivated by higher, one might even call them “knightly” ideals such as justice, chivalry, and honor.

It is notable that when Holmes breaks the law or refuses to turn in a suspect, it is normally for the sake of old-fashioned chivalry. We see this in “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” when Holmes neglects to turn in the murderer of a noted blackmailer because the victim was a scoundrel, and the poor murderer was a vulnerable woman. A similar case appears in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” where Holmes locates the murderer, the elderly father of an innocent young woman. Instead of turning him in, Holmes spares the family’s reputation, saying, “You are yourself aware that you will soon have to answer for your deed at a higher court than the Assizes.” Here we have justice, chivalry, and honor all in a nutshell. Sherlock trusts in a higher court for justice, while protecting a young woman’s honor. This is a long way from BBC’s Sherlock, rudely analyzing Molly Hooper’s lipstick and noting, to her face, that it compensates “for the size of her mouth and breasts.”8 Conan Doyle’s Sherlock may be a confirmed bachelor, but he doesn’t behave like a callous boor.

Utilitarian Turn

It is the absence of virtue that I think is the fundamental shift. Conan Doyle, modern as his stories may be, is still transmitting an older tradition. Sherlock Holmes, unlike his creator, was never knighted, but he stands in a noble line of heroes. Alasdair MacIntyre, has, of course, done so much to point out how modern ethical discourse has lost the coherence provided by accounts of human flourishing and purpose.9 Modern portrayals of Sherlock, much like modern people, have little sense of the classical meaning of virtue (which runs through Aristotle and Aquinas). Virtue ethics focuses on the development of excellence of character. Simply put, one cannot be a good person simply by doing good. However, one can conceive of Sherlock as a do-gooder, not in terms of his character, but in terms of his outcomes. Perhaps, then, the modern Sherlock is simply a hero in utilitarian terms. He may cause personal damage to those around him, but his big brain outweighs his hurtful behavior by producing more overall good through his detective work.

It’s worth noting that Christian ethics tends to focus on two main areas: rules and virtues. The Bible offers rules for life (the Ten Commandments, the Two Great Commandments, the Great Commission) that we are obligated to obey. The Bible also praises certain virtues (faithfulness, temperance, self-control, gentleness) toward which we should strive. Fairly foreign to the thought world of the Bible is the sort of utilitarian thinking that we find all around us. From government policies about health care to businessmen cutting corners “for the sake of their family,” it’s easy to find those who justify a “small wrong” for the sake of the “greater good.” As Sherlock has aged, his ethics seem to have grown more utilitarian.

Are Real Heroes Possible?

Yet I’m not certain that our shifts in moral philosophy are adequate to explain why modern Sherlocks have fallen so far. Perhaps the answer is simpler. Maybe the trajectory of Sherlock betrays a suspicion against the possibility of sustained virtue. Nolan’s The Dark Knight proclaimed that “You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”10 Perhaps, like the BBC’s Sherlock, we have lost our faith in the possibility of real heroes. The clever show anticipates my critique when Holmes quips, “Don’t make people into heroes, John. Heroes don’t exist, and if they did, I wouldn’t be one of them.”11

This modern Sherlock is wrong, of course, about Conan Doyle’s famous character and about the real world. I am heartened that even in our skeptical age heroes fill the page and screen. But it is dismaying that, so often, cleverness and cynicism are equated. It’s also clear to me that, if Sherlock’s case shows nothing else, virtue ethics will continue to become more and more of a mystery.

Philip Tallon, PhD, is the Dean of the School of Christian Thought at Houston Baptist University. He is the author of The Poetics of Evil: Toward an Aesthetic Theodicy (Oxford University Press, 2011) and the co-editor of The Philosophy of Sherlock Holmes (University Press of Kentucky, 2012). He’s sometimes on Twitter at @philiptallon.

NOTES

- The curious reader can investigate the book I co-edited with David Baggett, The Philosophy of Sherlock Holmes (University Press of Kentucky, 2012), for answers to these questions.

- I have avoided citations here, except to indicate the stories being mentioned. Readers can find many versions of Conan Doyle’s mysteries in print and free on the web, including here: www.sherlock-holm.es.

- Sherlock, Season 3, Episode 1, “The Empty Hearse,” directed by Jeremy Lovering, written by Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, BBC, aired January 19, 2014.

- Sherlock, Season 2, Episode 1, “A Scandal in Belgravia,” directed by Paul McGuigan, written by Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, BBC, aired May 6, 2012.

- Sherlock, Season 1, Episode 1, “A Study in Pink,” directed by Paul McGuigan, written by Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, BBC, aired October 24, 2010.

- Sherlock, Season 1, Episode 1, “A Study in Pink.”

- I can’t bring myself to rewatch the Guy Ritchie directed Sherlock Holmes (2009) and Sherlock Holmes: Game of Shadows (2011), so they may fit the pattern or not. I will leave this as homework for the inquisitive reader.

- Sherlock, Season 2, Episode 1, “A Scandal in Belgravia.”

- Notably, in After Virtue (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007).

- The Dark Knight, directed by Christopher Nolan, written by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2008).

- Sherlock, Season 1, Episode 3, “The Great Game,” directed by Paul McGuigan, written by Mark Gatiss, BBC, aired November 7, 2010.