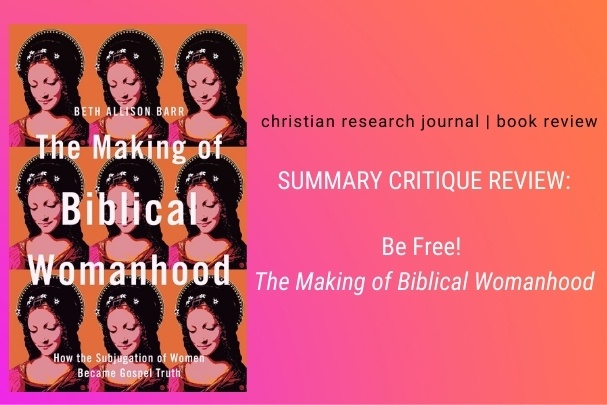

A Review of

The Making of Biblical Womanhood:

How the Subjugation of Women became Gospel Truth

by Beth Allison Barr

Brazos Press, 2021

This is an online-exclusive from the Christian Research Journal. For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

When you to subscribe to the Journal, you join the team of print subscribers whose paid subscriptions help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

“Go, be free!” concludes Beth Allison Barr in her recently released, best-selling book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth.1 In the intersection of her life in the classroom and the strictures placed on her by her local church, her beliefs about women radically shifted. Eventually, after a difficult conversation with the theologically unbending complementarian elders at her Southern Baptist Church, Barr and her husband, the youth pastor, were asked to leave. “This book is my story,” she writes, “a white woman whose experiences as a pastor’s wife and scholar have led me to reject evangelical teachings about male headship and female submission. I am fighting against patriarchy for women.” 2 Part medieval history, part personal narrative, and part examination of the condition of women in complementarian circles, Dr. Barr (a history professor at Baylor University) applies a feminist hermeneutic to Scripture and history. She purports to discover a malign patriarchal inclination, if not an actual conspiracy by complementarians, to write women out of the Bible, out of the church, and back into their homes to their highest calling by God as wives and mothers.

While Barr raises essential questions about the identity and role of women, her answer to what she perceives is the irredeemable evil of the patriarchy — to “Stop it”3 — is at the very least unsatisfying, if not impracticable, and, in the long run, theologically frail. Barr’s misrepresentation of biblical inerrancy, her definition of the patriarchy, her interpretation of history and the Bible, and her proposed solution, though emotionally evocative, offer a bleak ideological vision for women in the church and home. Ultimately, there are grave theological and historical problems with her work.

DEMOLISHING THE BIBLICAL CASE FOR PATRIARCHY

Barr, taking her lead from Judith Bennett, defines the patriarchy as “a general system through which women have been and are subordinated to men.”4 In Barr’s experience, this patriarchy has been articulated from many pulpits in biblical terms. “Women,” she writes, “were called to support their husbands, and men were called to lead their wives. It was unequivocal truth ordained by the inerrant word of God.”5 She finds this view troubling.6 Refuting Albert Mohler’s belief that “the pattern of history affirms what the Bible unquestionably reveals — that God has made human beings in His image as male and female….a beautiful portrait of complementarity between the sexes, with both men and women charged to reflect God’s glory in a distinct way,”7 she believes that Christians are actually “pretty late to the patriarchy game.”8 For Barr, there is no real difference between a biblical patriarchy — what many call complementarianism — and the kind found in ancient texts like the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which, against her own inclinations, “the prostitute Shamhat seduces Enkidu.”9

While admitting that “patriarchy exists in the Bible because the Bible was written in a patriarchal world,” Barr explains that the New Testament writers actually meant to undermine and subvert all patriarchy, not just its corruptions.10 Predictably, she bolsters that assertion with Galatians 3:26–28 and Sarah Bessey’s declaration that the “patriarchy is not ‘God’s dream for humanity.’”11 Then, in a series of “What if” questions, Barr demolishes complementarianism as she has defined it. “What if Paul never said this? Just like with the household codes, what if we have simply misunderstood Paul because we have forgotten his Roman context? What if we have confused Paul’s refutations of the pagan world around him with Paul’s own words?”12

Instead, she claims, Paul subverted pagan household codes and replaced them with a functionally egalitarian system within which men and women submit to each other,13 and women are able to hold the same church offices as men.14 Barr takes it as a given that Paul names Junia as an apostle in Romans 16,15 and that Phoebe, to whom Paul entrusted the letter of Romans, is not merely a “servant” but held the office of Deacon.16 All of this constitutes proof of Rachel Held Evans’s claim that Paul meant to “remix” Roman household codes, eradicating all patriarchal hierarchies.17

Turning to the question of Bible translation and inerrancy, Barr observes that the word “marriage” is not used in the Hebrew manuscripts. The translators of the King James Bible put it there, perhaps for nefarious reasons.18 They employed the word “wife” rather than “woman” because Reformation theology relegated women to the narrow sphere of home, husband, and children.19 Furthermore, she argues, complementarian Bible translators chose the use of male pronouns to refer to groups that include men and women.20 Finally, she claims, “the early twentieth-century emphasis on inerrancy went hand in hand with a wide-ranging attempt to build up the authority of male preachers at the expense of women.”21

The Historical Case Against Patriarchy

Barr begins each chapter with a personal example of how she experienced damaging patriarchal complementarianism — in the classroom with a misogynist student, for instance, or enduring a women’s retreat, or extricating herself from a relationship with a Bill Gothard disciple — interweaving those experiences with her expertise, the Middle Ages. Though women at the close of the medieval period were poised to settle into more spacious rooms, the Reformers read the Bible in such a way that hammered the nail into the coffin of women’s freedom.22 In fact, Barr argues, though women had to essentially abandon what made them distinctly feminine — their sexuality, their children23 — nevertheless the church welcomed them “to preach, teach, and lead throughout the medieval era.”24

Using the examples of Margery Kempe, Hildegard of Bingen, Mary Magdalen, Brigit of Kildare, and others, Barr avers that women did not identify themselves in the categories of Evangelical women today — as wife, mother, homemaker, and under the authority of a male pastor and husband. On the contrary, not only did they enjoy greater economic independence than their Reformation counterparts, they devoted themselves to God by entering communities of women, and sometimes ministered alongside men. Barr tells the story of fifth-century Saint Paula, who

seemed to believe she was practicing biblical womanhood, drawing strength from Jesus’s statement that “whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:37). Saint Jerome, her biographer, tells us that as the ship drew away from the shore, Paula “held her eyes to heaven…ignoring her children and putting her trust in God….In that rejoicing, her courage coveted the love of her children as the greatest of its kind, yet she left them all for the love of God.”25 Paula founded a monastery in Bethlehem and worked alongside Jerome to translate the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin.26

Though it did afford women certain kinds of freedom, Barr sees the Reformation, on the whole, as bad for women.27 The work peculiarly associated with women — beer making, for example28— came under the hands of men. Feminine identity shifted to the family as a woman’s sole vocation. Family groups began to sit together in church rather than the men on one side and the women on the other.29 Though everyone was free to read the Scriptures, men were recognized as the spiritual leaders of their homes, ruling over their wives and children.30

As the Industrial Revolution swept across Europe, the place of women became even more precarious. At first welcomed into the factory and office, gradually those spaces devolved into “public” spheres for men, and women were relegated to the “private” sphere of the home.31 Barr finds many harmonious notes between the purity crazes of the Victorians and the purity culture of the 1980s and 90s.32 The weakness of women in both cases required male protection. At the same time, women were cautioned not to inflame male lust by dressing provocatively.33 In one poignantly awkward account of girls at a youth camp being invited to wear big baggy T-shirts, Barr illustrates the continued unease of Christians about the female body, not to mention identity.34

IS “BIBLICAL” WOMANHOOD NOT, IN FACT, BIBLICAL?

The reader will likely find Barr’s case in The Making of Biblical Womanhood to be emotionally appealing and trenchantly persuasive. As noted, however, I believe that there are grave theological and historical problems with her work and would like to look more closely at three of her arguments — the origin of the patriarchy, the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, and translation. Barr imagines golden apostolic and medieval eras, mythical times of functional equality between men and women akin to the myth of the matriarchal prehistory, or Goddess Age.35 To make sense of the past, she ignores the distinction between pre- and postlapsarian patriarchies. Moreover, she mischaracterizes the doctrine of inerrancy and fudges over thorny translation issues. Ultimately, by reading history through a feminist lens, she misses the most obvious reason Christians persist in an antiquated view of women — that everyone in the world shared a norm that came to a grinding halt between 1880 and 1970, one that the Bible still articulates.

Cursed Patriarchy

A fundamental disagreement about the nature of the Fall exists between egalitarians and complementarians in their interpretations of Genesis 1–3. Egalitarians like Barr insist that the curse of the Fall — the man’s futility in working the ground, the woman’s pain in childbearing, their enmity with each other, her usurpation, and his tyranny — is the origin of patriarchy.36 Before the Fall, when God created man and woman in His own image, they were equal not only ontologically but also in role and function. In this view, the apostle Paul, when he commands all Christians to “submit to one another out of reverence for Christ” (Eph. 5:21 NIV), is restoring the prelapsarian egalitarian order. When a person becomes a Christian, individual identity as “slave or free, male or female, Greek or Jew” (see Gal. 3:28)37 comes to naught. Thus, according to egalitarians, all are equal in every way and should exercise their gifts in the church without regard to biological sex. To continue in a patriarchal system denies the gospel — the power of God to make everyone equal, to undo the ancient curse.

Complementarians find that the order in which God created — Adam before Eve — as well as Adam’s authority to name the animals, to tend the Garden, and to teach Eve the commandment of God (which either he fails to do, or she doesn’t believe him) to be the ideal (not mythical but truly Edenic and to be recovered in the eschaton) state to which both Paul and Jesus reach back as they consider marriage. Though Barr asserts that “marriage” was not thought of in the Old Testament, Jesus, if He can be trusted,38 certainly believed it was, naming the union of Adam with Eve as the first one (Matt. 19:4–6). Paul proclaims that Genesis 2:24 (which Jesus says is about marriage) refers to Christ and His church (Eph. 5:32). It is in that context that he admonishes wives to submit to their husbands “as to the Lord” (v22),39 a command he repeats in Colossians 3. He is not reinforcing the fallen order from Genesis 3 but reestablishing the prelapsarian order, grounding it in creation. Since Genesis 2:24 is about marriage and marriage is about the gospel, and Paul says that the submission of the wife to the husband is constitutive of that picture, then to disrupt or obscure that picture is to obscure the gospel. While I am grateful that Barr amasses data about a corrupt patriarchy that subjects women to abuse and ruin, I grieve that she doesn’t consider the theological implications of Paul and Jesus’ picture of the gospel in marriage, nor of God’s self-identification as “Father.”

“Translating” Preachers

In the section on translation, either because she doesn’t know, or because she is being dishonest, Barr plays fast and loose with her sources and terminology. Intimating that Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible into English from the Latin Vulgate is more faithful than the KJV translation from Greek and Hebrew,40 she neglects to note that Greek is inflected like English, allowing the use of the male pronoun in a collective sense to include groups composed of women and men together. Whether or not the language itself may then be considered “misogynist” is up for debate, but choosing as literal as possible a translation is not.

Similarly, Barr conflates the two dissimilar categories of translating and sermonizing. She notes that medieval preachers used gender inclusive language. As they “translated” texts that used male pronouns to refer to groups that included women, they would add “and women.”41 Whereas, she complains, the words “and women” do not appear in many passages of the KJV. The lack of the inclusive “and women” is taken as evidence of Reformation-era misogyny.42 Of course, good preachers in every age generally expound already translated texts, and where appropriate add “and women.” It should not be astonishing that medieval preachers would employ such a pastoral device, as indeed many pastors do today. Likewise, the outcry against the TNIV had to do with accurately translating the original texts, however offensive those texts are to modern ears.

Weaponizing Inerrancy

Barr alleges that the doctrine of inerrancy was invented by modern Evangelicals to oppress women: “Inerrancy introduced the ultimate justification for patriarchy — abandoning a plain and literal interpretation of Pauline texts about women would hurl Christians off the cliff of biblical orthodoxy.”43 Blaming Calvinists at Princeton University, Barr sees conspiracies in every library carrel: “For many, inerrancy meant not only that the Bible was without error but that it had to be without error to be true at all. Just like my youth Sunday school teacher, conservative evangelical leaders employed a slippery-slope mentality to weaponized inerrancy….How surprised I was to learn that Calvinist theologians at Princeton Theological Seminary actually led the inerrancy charge!” (emphasis in original).44

She rightly states that inerrancy is “the belief that the Bible is completely without error, including in areas of science and history,”45 but, like so many, assumes all inerrantists employ a woodenly literal interpretive method that disregards genre. People who have signed the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy, which Barr does not cite, can and do debate the genre of Genesis one and other texts. The Chicago Statement makes it clear that the “plain reading of the text” argument includes reading passages in the genre and for the intention that they were, in fact, written. “We affirm,” begins Article 18, “that the text of Scripture is to be interpreted by grammatico-historicaI exegesis, taking account of its literary forms and devices, and that Scripture is to interpret Scripture.”46 The doctrine of inerrancy — though clarified by the Chicago Statement — is affirmed by Scripture itself (2 Tim. 3:16) and has been articulated by theologians from the patristic age to the present.47 It affirms that the Scriptures in their original autographs are without error, are trustworthy on all the matters of which they speak, and are authored mysteriously by both man and God together. Just as John Calvin cannot reasonably be called a “radical Puritan translator,”48 neither is the doctrine of inerrancy a misogynist conspiracy.

What Really Happened?

It is undeniable that the Western Christian world saw seismic changes in the view of the person from the Reformation to the Sexual Revolution. While Barr tells one version of that story, thousands of others make a different case. Some say it is capitalism that saw the demise of female work. Others, like Barr, claim that it was the patriarchy. Complicating matters is the propensity of historians (Bennet blames medievalists in particular) to look to bon vieux temps — Golden Ages where women basically had it better than they do now.49 In many cases, this golden past reflects the light of the Goddess Myth,50 that there was a long-lost time of peaceful female dominance over men that was ultimately ruined by the patriarchy. The Goddess Myth has been roundly debunked, but so has the view that capitalism is to blame, or the patriarchy.51 History is too complicated to be explained by a single factor, never mind that comparing one age favorably to another without factoring in the assumptions of those very ages is a questionable practice. The historian is just as likely to read her bias back into the past as anyone.

Barr’s bias is clear. She believes that a woman’s work in spheres outside the home is preferable to her work associated with the home and her identity as a wife and mother. While Barr maligns this view, she never says why it is less preferable to a life in the factory. Moreover, Barr has a view of marriage and family closer to secularists of this moment than that of Christians across denominational lines. Take this popular level explanation, by a platformed academic, who admits that men and women had a fairly consistent view of gender and family life until 40 or 50 years ago. Regarding the discomfort so many people still feel about their home life, this academic concludes:

Many of our problems arise not because we’ve changed too much but because we haven’t changed enough. One big cause of marital stress and divorce is the failure of some men to change their household roles enough to match the change in women’s work roles. Another cause, researchers are finding, is that couples tend to fall into traditional gender roles after the birth of a child, which can produce resentment in both parents. And one of the main dangers to children after a divorce is the old-fashioned notion of many men that their obligations to their kids end when they no longer enjoy the services and support of the children’s mother.52

The solution, of course, is more social services and free state-financed infant care. As a Christian, I wonder that Barr prefers this view of the relationship between men and women. Doesn’t the Scripture vision of the restful love between Christ and the church offer a much more compelling vista for Christians to contemplate?

Going and Coming

I appreciate that Barr details the distressing cultural clash between the church, the world, and the academy. For whatever reason, she found herself in a congregation with a narrow view of women, one that did not allow her to teach boys and men under any circumstance. Though I don’t share that view, and I think she mischaracterizes the motivations and beliefs of complementarians in general if not those of the elders of her church in particular, I can sympathize with the pain of enduring the clash of competing ideologies. Likewise, I appreciate Barr’s effort to engage with the history of the church. So many Evangelicals do think that church history began in 1990. They’ve heard of Calvin and Luther but have read only I Kissed Dating Goodbye.

The Making of Biblical Womanhood is a testament to the cultural predicament Christians faced in the last century and their continued unease in the present. On the one hand, they believed that the Bible was the word of God that had authority to shape their lives, but on the other hand, they lived in a world whose assumptions about the nature of the person — identity, sexuality, work, the body, everything — radically shifted away from its Judeo-Christian roots. They went to church on Sunday and to school on Monday, and the night hours were not long enough to reconcile those two realms. Not to mention that while Evangelicals fretted about AIDS and transgenderism, Josh Duggar allegedly nursed an addiction to child pornography.53 Do we really have to think about whether or not women can speak and lead when so many women have been abused by elders and pastors? Maybe it really is time to “stop it,” and “be free.”

As a lifelong lover of the Scriptures, I believe that there is a greater call than to “stop it.” The God we meet in the Bible — from the first opening words, to the very last — invites women into a vibrant community where their work and lives are woven into the great tapestry of Christ’s love for His church, and the church’s astonishing trust in Him. Freedom for women — and for men — is to take one’s place in the glad throng, to have one’s heart remade in the image of Christ who is God. From the world’s perspective, this “taking of a place” and the “remaking of the heart” looks like a narrow, even cruel way. It is a toiling in obscurity, a relinquishing of the self, a painful obedience. The Christian woman needs no mythic past upon which to base her present life. Rather, she looks forward to a kingdom (with a King), a city, Eden restored, an eternity in perfect communion with God. “Come,” says the Spirit and the Bride, “Let the one who is thirsty come; let the one who desires take the water of life without price” (Rev. 22:17).

Anne Kennedy, MDiv, is the author of Nailed It: 365 Readings for Angry or Worn-Out People (SquareHalo Books, rev. 2020). She blogs about current events and theological trends at Preventing Grace on Patheos.com.

- Beth Allison Barr, The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2021), 218.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 33.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 206.

- Judith Bennett, History Matters: Patriarchy and the Challenge of Feminism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 55, as quoted in Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 14.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 12.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 12.

- Albert Mohler, “A Call for Courage on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood,” Albert Mohler (blog), June 19, 2006, https://albertmohler.com/2006/06/19/a-call-for-courage-on-biblical-manhood-and-womanhood, as quoted in Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 24.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 12.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 22.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 35–36.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 36–37. Barr cites Sarah Bessey, Jesus Feminist: An Invitation to Revisit the Bible’s View of Women (New York: Howard, 2013), 14.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 56.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 49–51.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 63.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 65–67. Whether or not Junia was an apostle is contested among scholars and is by no means a determined fact as Barr suggests. Daniel Wallace’s article “Junia Among the Apostles: The Double Identification Problem in Romans 16:7” is a fair examination of the issues. https://bible.org/article/junia-among-apostles-double-identification-problem-romans-167.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 67–68. Barr herself admits the word can be used either way (see 65–68).

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 47. Barr cites Rachel Held Evans, “Aristotle vs. Jesus: What Makes the New Testament Household Codes Different,” Rachel Held Evans (blog), August 28, 2013, https://rachelheldevans.com/blog/aristotle-vs-jesus-what-makes-the-new-testament-household-codes-different.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 148–150.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 149–150.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 130–33.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 189.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 114.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 90–91.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 90; cf. 90–95.

- Barr cites Jacobus de Voragine, “The Life of Saint Paula,” quoted in Larissa Tracy, Women of the Gilte Legende: A Selection of Medieval Saints Lives (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer, 2014), 47.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 79.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 113–17.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 109–110.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 125–26.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 104–105.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 165–66.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 155–57.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 156–57.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 154–56.

- See Barr, Biblical Womanhood, chapter 3, “Our Selective Medieval Memory.” For those interested, John Elliot debunks the myth of egalitarianism in “Jesus Was Not an Egalitarian: A Critique of an Anachronistic and Idealist Theory,” Biblical Theology Bulletin 32, 2 (2002): 75–91, https://doi.org/10.1177/014610790203200206; and Mary Ann Beavis critiques Elliot’s argument in “Christian Origins, Egalitarianism, and Utopia,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion23, no. 2 (2007): 27–49, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20487897.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 28–32.

- I paraphrase Galatians 3:28.

- Barr throws the trustworthiness and divinity of Jesus into question in her claim that a woman “won an argument with Jesus.” Biblical Womanhood, 76.

- Unless noted otherwise, Scripture quotations are from the ESV.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 139–41 (see 139–150).

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 141.

- See Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 139–50.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 190.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 188, 189.

- Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 188.

- The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is accessible at https://www.alliancenet.org/the-chicago-statement-on-biblical-inerrancy.

- John Woodbridge’s “Did Fundamentalists Invent Inerrancy?” is a helpful historical and theological look at the origins of the doctrine and what it does and doesn’t mean. TGC, August 3, 2017, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/did-fundamentalists-invent-inerrancy/.

- See Barr, Biblical Womanhood, 145.

- Bridget Hill, “Women’s History: A Study in Change, Continuity, or Standing Still?,” Women’s History Review 2, No. 1 (1993): 5–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/09612029300200018.

- Robert Sheaffer aggregates a list of scholarly rejections of Marija Gimbutas’s ‘Idyllic Goddess’ theories in his piece, “Some Critiques of the Feminist/New Age ‘Goddess’ Claims,” The Debunker’s Domain, revised August 1999, https://www.debunker.com/texts/goddess.html.

- Hill, “Women’s History.”

- Stephanie Coontz, “The Family Revolution,” Greater Good Magazine, September 1, 2007, https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/the_family_revolution.

- Rasha Ali, “Josh Duggar Will Be Released Pending Trial: Everything We Know about His Child Pornography Charges,” USA Today, updated May 5, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/celebrities/2021/05/03/josh-duggar-child-pornography-charges-what-we-know/4923762001/.